Over the course of this semester, the point I keep coming back to is that design is problem solving at its core. I have found this in my creative life (sewing and ceramics allow for a lot of trial and error), my work life (stand-up comedy for children really isn’t a thing for a good reason) and now my academic life. For some reason, I never thought about how learning was designed—design was limited to physical things like fashion and furniture.

So I started thinking about the problems I have encountered or things I have spent a lot of time trying to get people to learn over the course of my career as a developmental editor and sort-of writing coach for people who want to write novels, picture books, and scripts for kids. I have noticed over the years that there is a tendency, especially when writing for the youngest kids, to ignore causal connections between actions. And through many iterations, What Upon a Time was born as a way to nudge people toward better conjunctions.

Let’s start with the final game design, so I can explain how I got here.

The Final Design

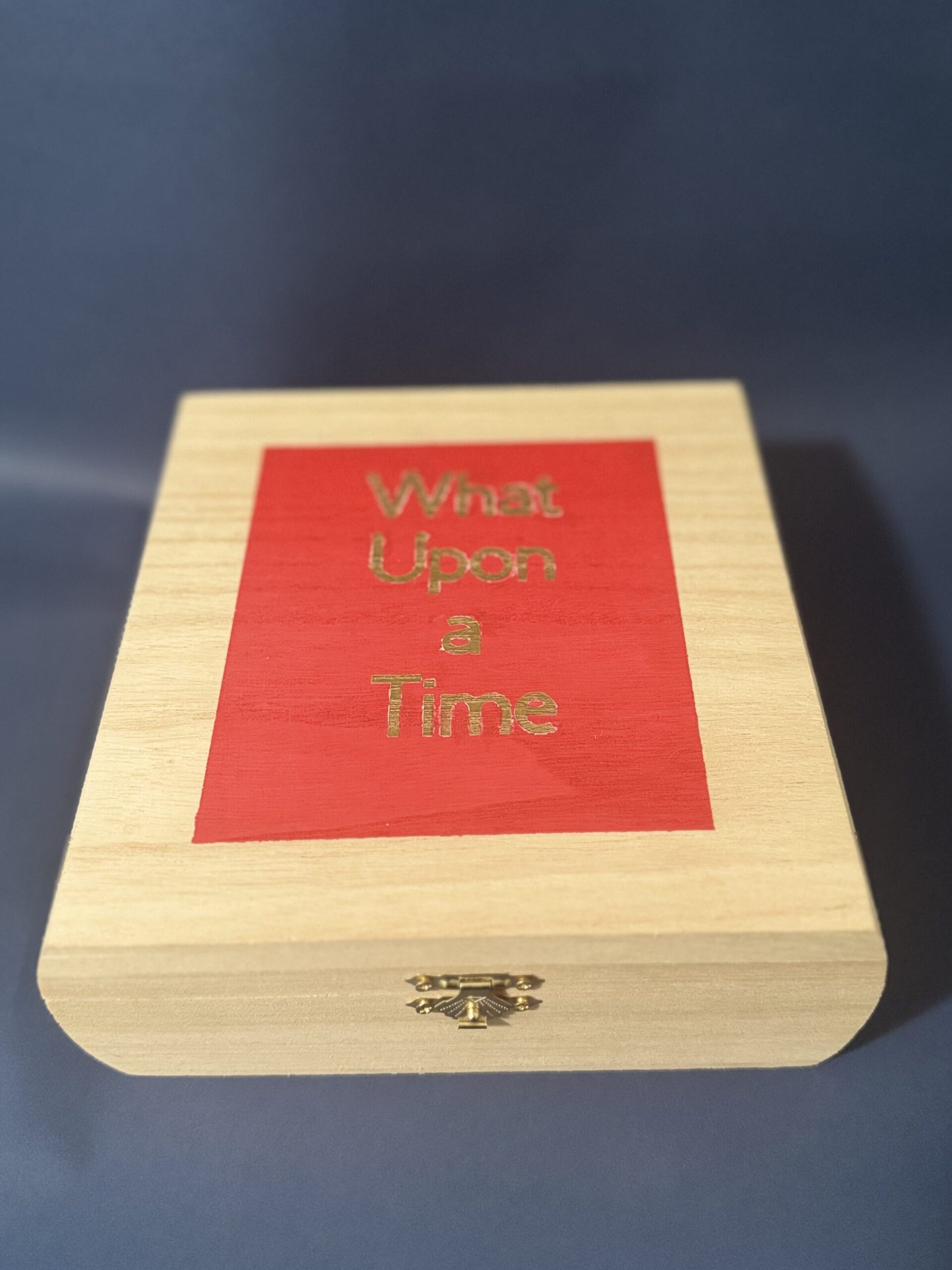

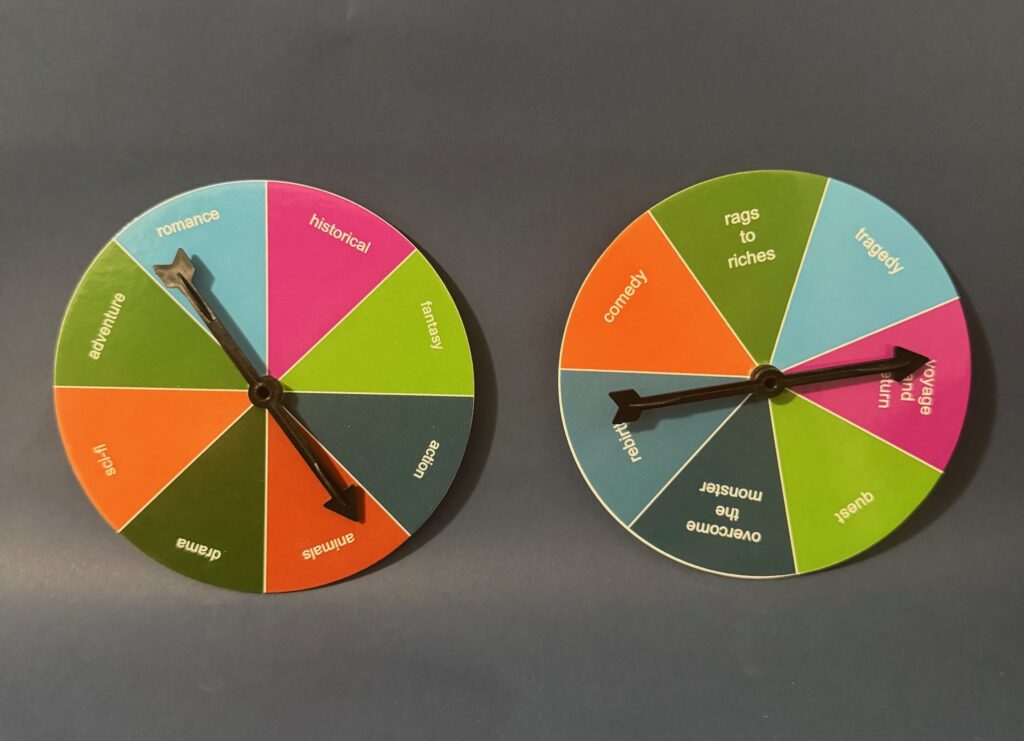

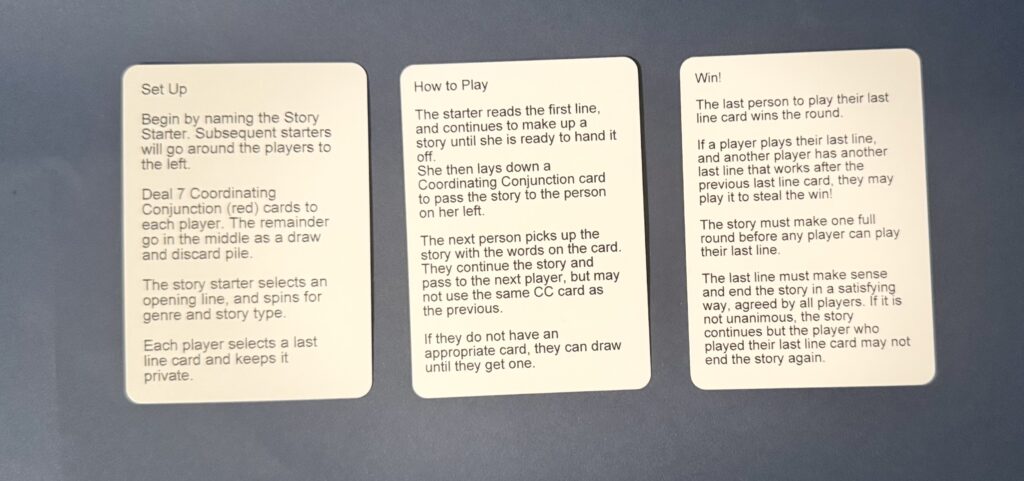

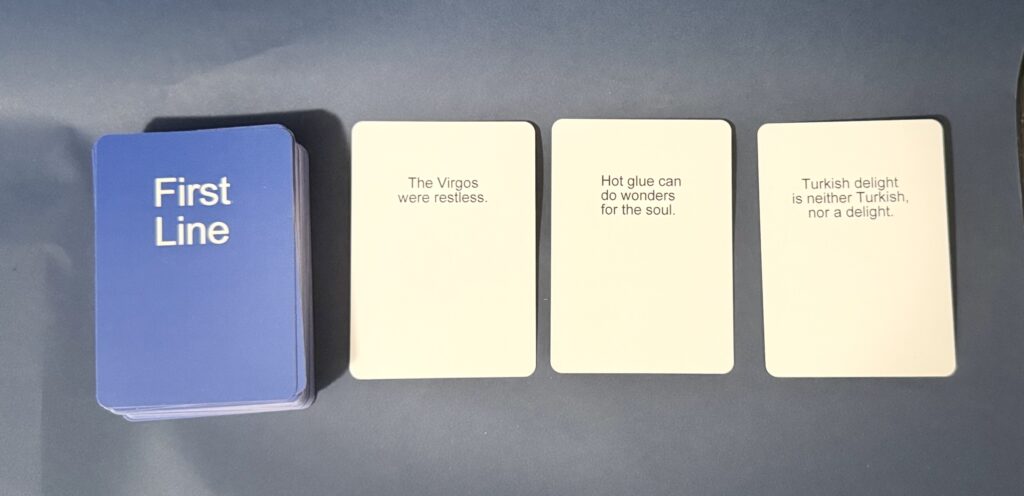

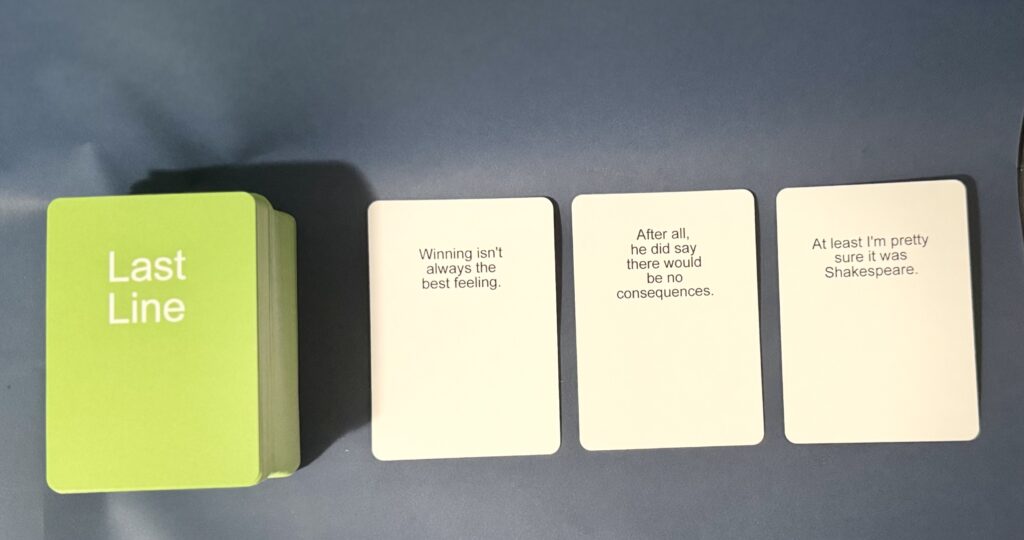

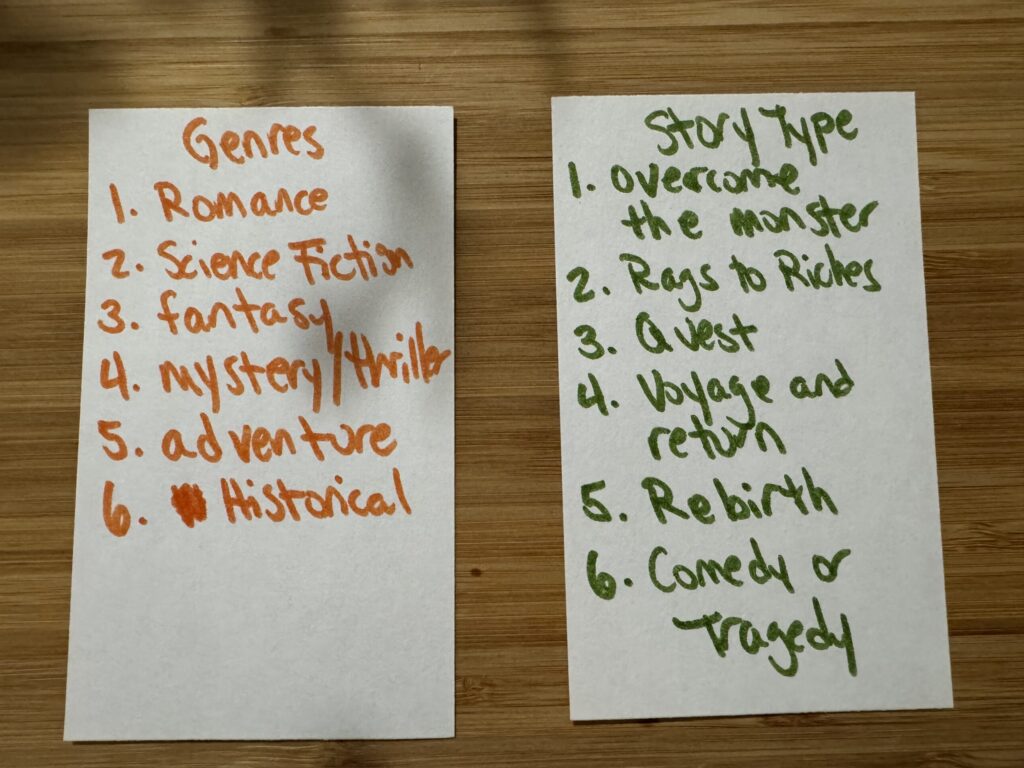

What Upon a Time is a storytelling card game. We have a box with 3 decks of cards: First lines, last lines, and coordinating conjunctions (none of which are “and then”) and two spinners. The story starter spins for story type and genre, then starts the story off with their first line.

They then hand off the storytelling by laying a linking phrase card. The next player picks up the story and it continues around all the players. The first player to incorporate their last line and lay their card wins the round.

I have edited or critiqued thousands of manuscripts over the years. And in that time, I discovered that many authors presented lists masquerading as stories. For example:

My name is Axl and I am 6 years old! Today I went to school and then we played at recess. I love recess because we get to run around. And then we read books. And then I came home and fed my dog. I took him for a walk, and we saw 6 squirrels making pizza! And then we had a bath and went to bed.

Because this was such a persistent issue, it was a problem that I needed to solve so I could give the same note quickly and easily. I didn’t know it at the the time, but I had designed a way to easily explain to writers of all experience levels that action leads to reaction, which leads to a decision the character makes, which leads to another action. Here is a diagram:

Sometimes, the characters make good decisions, and sometimes, they make terrible decisions (I have come to realize that the Coen Brothers are masters of making characters who only make terrible decisions). And those decisions determine what the character will do next–their next action–to which they will react.

For example, a character, let’s call her Nadia, goes to a coffee shop to meet her friend Barack (action). She sees a sign on the door that says they are closed. Nadia can react to this in lots of different ways, and this is often internal. She could be neutral (there are other coffee shops she likes), she could be happy (the owner was pretty mean), or she could get angry (they owed her a free coffee!). These reactions then lead to more action. For instance, she could call Barack and say “hey the place is closed, let’s meet somewhere else,” or she could start pounding on the windows, demanding they open up, or she could slump to the ground and wail in despair or lots of other actions. You get the idea.

But it is not a very interesting story to say Belinda went to the coffee shop and then she saw it was closed and then she pounded on the windows and then she and Archie went somewhere else. And then has a very loose relationship between actions.

I share often this video of The South Park Guys talking to a group of students at NYU’s Tisch School for the Arts about turning all the and thens into therefore or but.

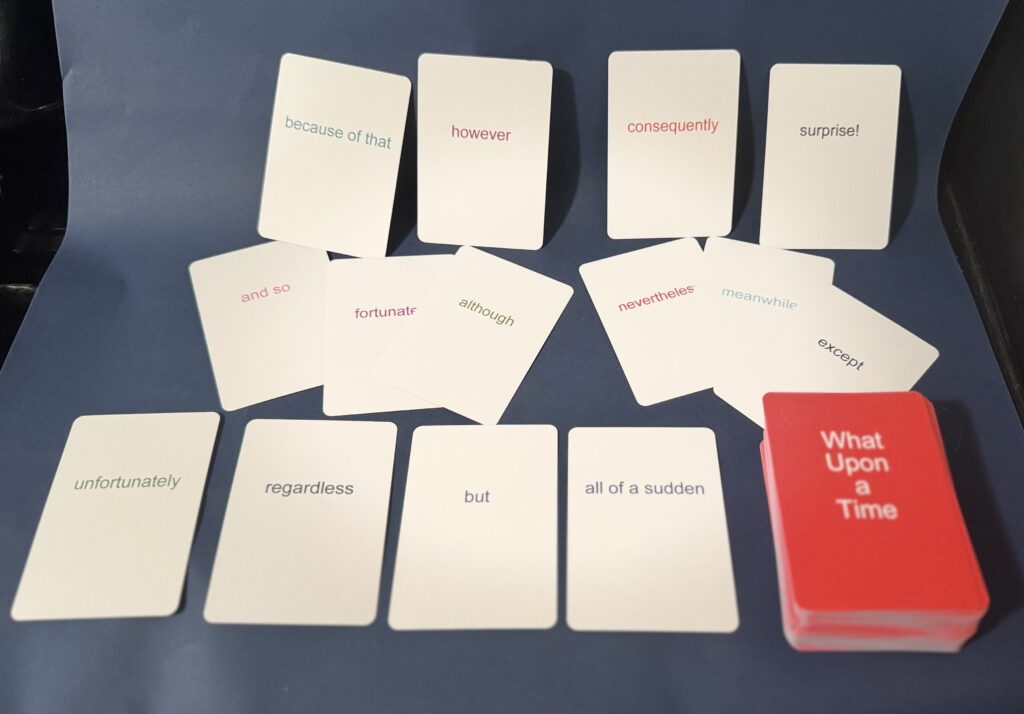

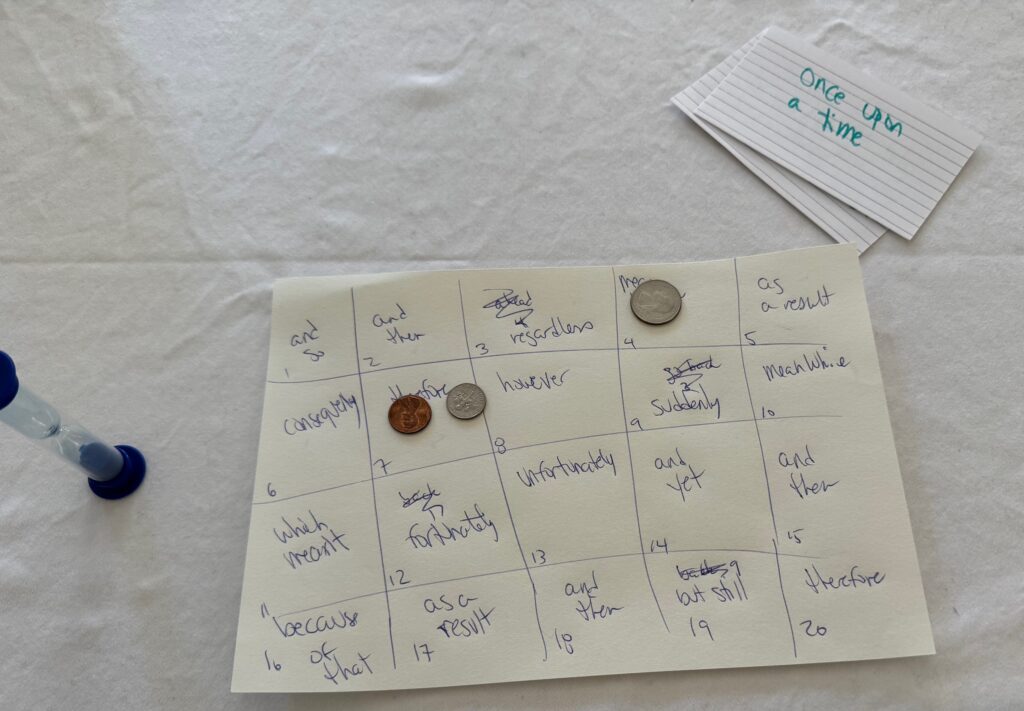

It’s a very effective switch to flip, and in the course of designing this game, I have focused in on many phrases like therefore and but that indicate change, or progress a story from one thing to the next. They cause something to happen. (These are called coordinating conjunctions, but that makes this all sound too academic, so here we’ve been calling them “linking phrases” which sounds more game-like, at least to me.)

Initially, there was going to be some sort of penalty in my game design for using the phrase and then. But as I tinkered and play-tested, I settled on just not including that particular phrase on any cards. The intent is to practice good storytelling, not punish people for trying. It also eased the flow of the game during testing to leave it out.

Over the course of designing this game, I have learned that for a lesson as direct as this (use this phrase, not that one) simplicity is key. The message becomes clearer, and too many rules about when, why, and how to use specific coordinating conjunctions didn’t let the game roll the way it wanted to. There needed to be as few rules as possible while maintaining a quick pace with few to no interruptions.

I’ve also realized just how much change can happen to a design as it is iterated and tested. At first, I was thinking of this as a game for kids. But kids are still learning grammar and storytelling for the first time. I don’t want to make them feel like it’s hard or not-fun. And the people I was seeing the “and then tendency” from were all adults. So I changed tack and made this into more of a party game for grown-ups.

Early Iterations

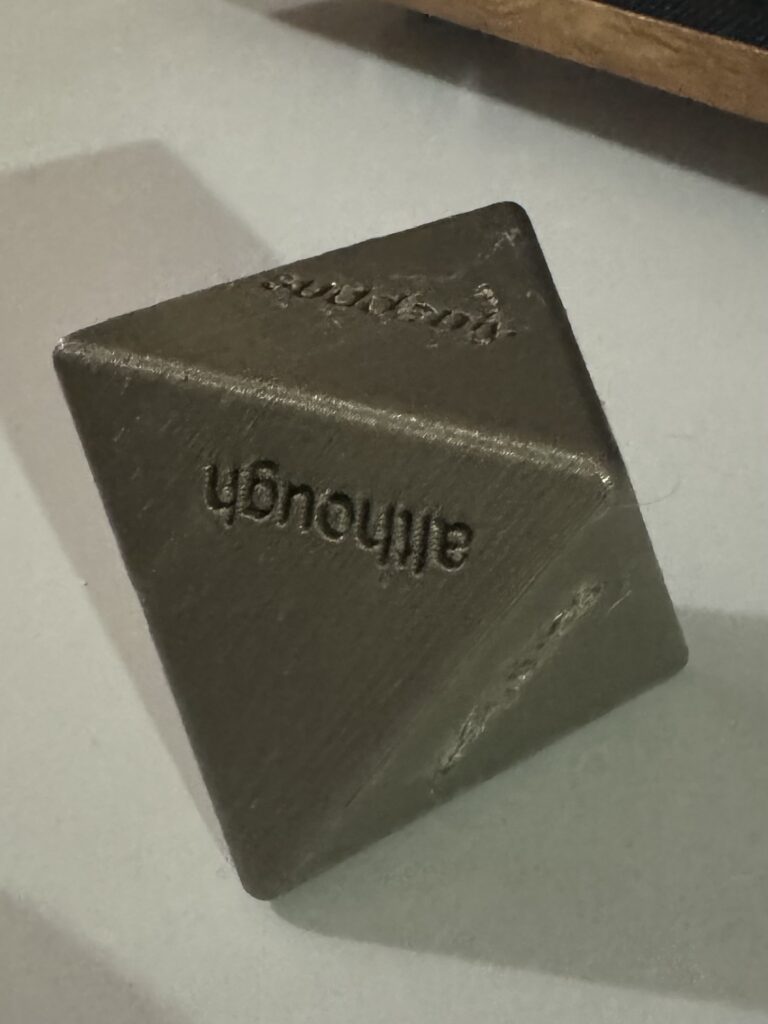

This all started as a dice game, with the linking phrases on each side of a large die. But rolling the die between storytellers slowed the game down and limited the number of coordinating conjunctions I could include.

Then a it became a dice-and-card game, rolling dice to choose genre and story type from a list. But those were hard to keep referencing throughout the storytelling. And so I landed on spinners, which are not just practical, but add a fun game element.

At one point we tried a board out to see if moving along a path would add some exciting unknowns into the game (go back, jump ahead) and to indicate a clear winner. There were timers involved (that lasted less than the one minute of sand in the timer). Rules changed and methods evolved. But the intent to add cause and tension to stories never changed.

The framework around the original idea changed many times, but the goal never did. And that may be the hardest part about learning design: Keeping the focus on the intended learning, and changing the project around it can be tricky. The learning achieved in my final game may not be as overt as it was initially dreamed up, but ultimately, by practicing the behavior I hoped to correct, the design achieves its goal.